While the provincial budget for 2014 was all about spending government money, the budget speech did raise one issue that the provincial government appears intent on cutting dramatically.

A key component of the province’s net debt relates to unfunded pension and other post-retirement liabilities. Despite an investment of more than $3.6 billion, the liabilities have continued to grow. As of March 31, 2013, they accounted for 67 per cent of net debt. By 2016-17, they will account for 85 per cent of net debt – almost $9 billion.

The provincial government has been talking about the unfunded pension and benefits liabilities for a couple of years now. It’s a hot issue among business groups like the employers’ council or the Canadian Federation of Independent Business.

As regular readers know, the board of trade is keen to deal with the unfunded liability, too, even if the president or whoever wrote her column in last week’s Saturday Telegram don’t appear to understand what it is all about.

For whatever reason, business groups get quite agitated about public sector workers and their pensions. Other public debt doesn’t get them quite as worked up and, as the board of trade demonstrated quite clearly, there’s a fair bit of misinformation about the unfunded pension liability.

In this second post in the Budget Basic series, let’s take a look at public sector pensions and put them in a wider context. Misinformation never leads to good public policy but right now, pretty well all the anti-pension commentary is based on some amount of misinformation.

Six Pension Plans

The unfunded pension plan liability involves six specific public sector pensions and - since 2003 - an unfunded liability for health and life insurance benefits for retirees.

The government contributes different amounts for health and life insurance benefits for different employees after retirement but has no funds set aside to cover those benefits. Hence, the health and pension benefits are entirely unfunded.

Before 1980, the provincial government paid any pensions for its public sector workers out of the provincial government’s annual general revenues. Those revenues included employee contributions under individual statutes for each of the pensions. The Public Service Pensions Act is typical of these. That’s pretty much what the government had done since well before Confederation.

The Pension Funding Act of 1980 created a pooled pension fund with the province’s finance minister as trustee for five of the pension plans. The Memorial University Pension Plan is managed by the university using its own pension fund.

For the other five plans, both employees and the provincial government contribute to a pool of funds that is invested under the direction of a pension investment committee. The committee members include representatives of the provincial government (the employer), public sector unions, retirees and a non-government/non-labour member.

The provincial government uses the fund and the proceeds from the investments to pay pensions for five of the pensions. There are five public sector pensions covered by the fund:

- The Public Service Pension Plan is the largest plan in terms of number of members.

- The Teachers’ Pension Plan is for the province’s public school teachers.

- The Uniformed Services Pension Plan provides pensions for members of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, provincial corrections officers, and regional firefighters in St. John’s.

- The House of Assembly Pension Plan provides pensions to former members of the provincial legislature.

- The Provincial Court Judges Pension Plan is for retired provincial court judges.

Current Status

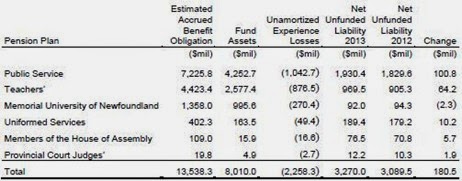

According to the 2012 Public Accounts, the plans have different levels of funding. The chart below is taken from Volume 1 of the 2012 Public Accounts.

Funded and Unfunded Liability

The six pension plans represent a cumulative liability of $13.5 billion. The full amount of the pension liability is typically not included in discussion of public debt because a portion of it is funded. That is, the government has set aside funds that are specifically earmarked to cover the liability. In that sense, it is like sinking funds for borrowings and other types of debt. The government has set aside money – called sinking funds - specifically to pay off certain debts.

Note that this isn’t the same as net debt. In that calculation, accountants use all assets, including money that is earmarked for other spending, in order to create a theoretical picture of what liabilities could not be met with assets. The public debt figures SRBP typically uses include a deduction for sinking funds and pension funds. Thus, what is left – $18 billion current – is in largest part debt for which there is no money already designated to pay.

About 59% of the pension liability is funded (money set aside to meet the obligation) and 24% is unfunded. Some of the plans are in relatively better shape than others. The MUN plan is 73% funded. The two largest plans – PS and Teachers – are funded at 58%. The uniformed services plan is only 40% funded. The two worst-funded plans are the judges (25%) and the MHA plan (15%).

Experience and Rates of Return

There is also an amount in that chart – $2.2 billion – that represents the difference between what the pension committee’s advisors expected the investments to earn over time and what it actually did. The government hasn’t actually included that amount in its calculation of the unfunded liability but it is part of problem. What you should remember when looking at that number, though, is that some years the fund will actually make more money from its investments than it figured. Those earnings can reduce the total amount of the unfunded liability, including the so-called experiential losses.

To give you a sense of how the committee’s investments have been performing, take a look at this table and the paragraph taken from the 2012 committee report.

9.3 Annual rates of return

The asset mix strategy as of December 31, 2012 of 75% equities, 20% fixed income and 5% real estate was adopted based on the plans’ going concern funded ratio and the need to manage the growth of the unfunded liabilities. To further diversify the impact of investment volatility and enhance expected returns, specific investments are allocated among broad asset classes. While returns in excess of the discount rate will not be achievable every year, the Fund’s annualized rate of return over the past 20 years is 8.4%. This is higher than both the policy benchmark return of 7.8% and the discount rate of 7.25% used in the 2009 actuarial valuations. The fund’s annualized return over 10 years is 7.1% (v. policy benchmark of 6.8) and over 5 years is 2.2% (v.policy benchmark of 2.1). The following graph illustrates the variability in annual rates of return over the past 20 years.

What that means, in simplest terms, is that the committee has invested its money in a way that reliably earns the largest amount over the long term. That’s important: organizations manage their pension with the long-term in mind.

What’s also important to note in that report is that the committee is actively working to deal with the unfunded liability. The committee can only work within the limits set by the pension legislation but the committee is working to improve the situation. It’s not as though people haven’t noticed the unfunded liability before now.

Tackling the Unfunded Liability

The provincial government has been paying some attention to the unfunded liability as well. While you wouldn’t know it from the way some people talk, the first effort to add extra cash to the pension fund came in 1997. Since then, both the Liberal and Conservative administrations have added extra cash to try and change the funded/unfunded ration.

To get a sense of what has been going on, take a look at this chart. it shows the funded and unfunded pension liability. Look at the left side of the chart and you will see that it wasn’t all that long ago that the unfunded part of the pension liability was larger than the funded bit.

Hibernia first oil came in 1997. I’s no coincidence that as the provincial government started to get significant new revenue, that it also started to tackle its debt problem. There’s also no coincidence that the government started to tackle the pension problem as it got closer to the point when more and more public servants started to retire.

In 1980, retirement for most public servants was a long way off. As the baby boomers who made up the majority of the service started to get closer to retirement age and then to retire, the pension liability switched from being a distant problem to one that was right around the corner.

The single biggest improvement in public sector pension funding in Newfoundland and Labrador in the past 20 years was the injection of $2.0 billion in a single federal-government transfer in 2005. That didn’t get much play publicly as the Conservatives found it more important for them to claim the 2005 federal transfer was much more than it was. Finance minister Tom Marshall, for example, has claimed the 2005 transfer helped produce annual surpluses long after his predecessor got the cheque, cashed it and deposited the money in the pension account.

But that 2005 transfer from the federal government was the single biggest change in the pension funding in the past 20 or 30 years. In fact, clause six of the 2005 agreement that covered the transfer specifically ear-marked it for debt reduction.

An Opportunity Lost

The result of that one-time cash injection was that the unfunded portion of the pension fund was at its lowest point in a decade. In 2008 and 2009, the combined unfunded pension and benefits liability was about $2.9 billion.

That was the same time when the provincial government booked enormous surpluses due to record-high oil prices. It’s also the same time that the provincial government categorically refused to take two steps that would have helped deal with the public debt. Tom Marshall – on behalf of his cabinet colleagues - specifically rejected the idea of legislation that would force him to table a balanced budget. He and his colleagues also rejected the idea of putting some of the oil windfalls aside in an investment fund.

Recall that since 2007, the provincial government has had upwards of $5.0 billion in cash and temporary investments at some points from those oil windfalls. It could have easily earmarked some of that money over a long time to pay down the unfunded pension liability.

Some might claim that the government couldn’t do that since it also had to spend money on the so-called economic stimulus after the recession in 2008. Bear in mind, though, that the government booked those extraordinary levels of cash-on-hand as it was spending on the surplus. What’s more, a sizeable chunk of the “stimulus” spending was actually carry-over from previous years that remained unspent. On top of that the provincial government as able to increase spending to admittedly unsustainable levels because of continued record-high oil prices.

In short: the provincial government had the money to tackle the unfunded pension liability. They just wanted to do something with it besides tackling the debt. To give you a sense of how a different policy could have led us to a different spot, take a look at the SIDI simulation SRBP ran last April:

The SIDI simulation included:

- a steady, sustainable increase in spending each year,

- an unprecedented, sustainable capital works program,

- a $3.675 billion real decrease in public debt,

- the prospect of a complete elimination of public debt within a decade, and,

- an income fund that would continue to grow with further oil money and generate new income for the provincial government for as long as the fund existed.

It’s all a matter of political will that would deliver effective public policy. That will has been missing for more than a decade.

The Causes of the Current Problem

The Auditor General included an extensive report on the unfunded pension liability in his report on the province’s public accounts for Fiscal Year 2012 (ended 31 March 2013).

Two major developments since 2005 combined to create the current problem in unfunded pension and benefits liability and both are the result of deliberate provincial government policies. We’ve already talked about the first one, namely the conscious decision to reject any concrete debt reduction policies.

The second one is spelled out clearly by the Auditor General:

As Chart 8 indicates, the number of Public Service Pension Beneficiaries has increased from approximately 51,000 in 2003 to approximately 70,000 in 2012 - an increase of 19,000 or 37%. Of this increase, 7,700 or 43% is the result of an increase in the number of individuals receiving pension benefits. The increase in the number of beneficiaries has contributed to the increase in obligations related to employee future benefits.

Here’s Chart 8:

That’s right.

The provincial public sector pension plans have 19,000 new beneficiaries – new employees and retirees - in 2012 that they didn’t have in 2005.

Regular SRBP readers have heard about the massive increase in public sector employment before. Together with the massive increases in public spending since 2006, this is what has been driving the economy lately. When people like economist Frank Coleman talk about the great things that have happened since 2003 and the thriving economy, they are talking – knowingly or not – about massive, unsustainable increases in public spending based almost exclusively on one-time cash from oil and minerals.

Curious Silence

Not surprisingly, that information is missing from all the negative comments about pensions by the provincial government, business groups, and others. The same people who profited and who continue to profit from unsustainable public spending are now clamouring for a dramatic cut to public sector pension benefits that will adversely affect only public sector workers.

Public debt is one of the biggest problems facing the province. Unfortunately, the level of misinformation and misunderstanding about public debt has served to cloud the issue or, in the case of pension liabilities, threatens to lead people to support bad public policy.

Next in the Budget Basics Series, we’ll look at some ways we could tackle the public debt problem while we still have time to do so.

-srbp-