Tom Osborne

was in Ottawa

on Tuesday with his fellow finance ministers trying to squeeze some extra

cash out of the federal government.

The wealthiest

provinces in Canada – Alberta,

Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador – are looking for some changes

to the Fiscal

Stabilization Program that would give them extra cash. They’ve given up on changes to the

Equalization program since it is intended to help poorer provinces deliver

essential services at roughly comparable levels of taxation.

FSP “enables the federal government to provide financial

assistance to any province faced with a year-over-year decline in its

non-resource revenues greater than five per cent.”

Provinces may submit a claim to the Minister of Finance as

late as 18 months after the end of the fiscal year in question or may also

submit a claim for an advance payment based on as few as five months of data

for the fiscal year.

The program doesn’t compensate provinces for losses due to

changes in provincial taxation rates. A drop in resource revenues is taken into

account only if and to the extent that the annual decline in revenue exceeds 50

per cent.

As Osborne’s financial update for 2019 indicates, though, a bit

of extra federal cash won’t fix the problems Osborne has.

Dependence on Oil

Tom’s main financial problem is that the

provincial government is heavily dependent on oil royalties.

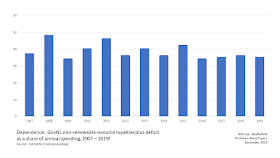

To see this, take a look at an updated version of a familiar

SRBP chart. It shows deficit, oil

royalties, and mineral royalties as a share of spending. The numbers are from The Estimates, the

budget document that uses cash accounting.

The chart covers the period since 2007, which is basically the time the

provincial government started to get massive amounts of oil money and started

spending all of it and more besides.

All that the Liberals have been able to do since 2015 is

stabilise the dependence at a high number (around 35%). They haven’t been able to reduce the

dependence and they certainly have no plan to reduce it. As a result, the provincial government is

constantly at risk of the sort of deficit surprises. That makes it hard to plan with any degree of

certainty. It will have consequences for the province’s credit-worthiness, if

not now than in the near future.

To put Newfoundland

and Labrador’s position in perspective, here’s a chart from 2015 by Alberta

economist Trevor Tombe, who first used this measure of dependence to assess

Alberta’s budget plans.

Newfoundland and Labrador has a higher level of dependence

on oil royalties than Alberta does. Just using a rough estimate of the Alberta figures,

on average the local vulnerability is about eight to 10 percentage points above

that of Alberta between 2007 and 2015.

Allowing the forecast Tombe shows in red beyond 2015, you can see that

Newfoundland and Labrador is as bad or worse than Alberta still.

Not good.

Masters of Our Own House... whether you want it or not

The other problem Tom faces in dealing with Ottawa is

political. This comes in two aspects.

One is provincial. Like Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador

is in this financial state solely because the provincial government – by and

with the support of the province’s people – decided to spend money this way and

refuses to change. They all know that revenues

from oil and minerals are notoriously unpredictable. Yet, they continued. In Newfoundland and

Labrador, as in Alberta, any attempt to reduce that dependence on oil through

reduced spending, higher taxes, and so forth have been met with savage public

opposition.

Even people who publicly claim they understand the financial

problems do not support any efforts by the provincial government to correct the

dependence on its own. They have a

variety of rationalisations for their position but most of them start from the

assumption that the government cannot deal with the problem without causing

devastating consequences to the provincial economy and its people.

Those who think that way advocate a federal bailout. Members of this particular group include

everybody from the current premier to a former Clerk of the Executive Council,

a former senior political advisor to two Progressive Conservative premiers, a

local celebrity musician, and a hockey bag of others from other backgrounds. They are not stupid nor are they slackers.

They don’t agree on many other things, mind you. On Muskrat Falls, for example, some of them

have been diametrically opposed to each other for years. But on the provincial government’s financial problem,

they agree the federal government must fix it and that there is nothing the

provincial government can or should do but fight with Ottawa.

They don’t know that this is so because none of them have looked

at the whole problem. They have simply

assumed it is too big to manage.

Some of you might object that Des Sullivan disagrees with

Osborne, based on Sullivan’s most recent

blog post. Sullivan laces into

Osborne for the recent financial update but note that what he criticises Osborne

for is, in every respect, what every one of Osborne’s predecessors has been

doing for the past decade or more. That’s

a sign that Osborne is in line with public sentiment generally and, to be sure,

it is in line with Sullivan’s own support - demonstrated in post

after post after post - for a federal bailout to resolve the province’s

financial problems.

That’s really a crucial part of the context for Tom Osborne’s

trip to Ottawa. The provincial government has an enormous financial problem

that is rooted in the provincial government’s own decisions. Yet, very few

voices in the province - and Sullivan isn’t really one of them - are calling

for the provincial government to gets its own house in order. Once, they said they wanted to be maîtres chez

nous – masters of our own house - but at the first sign of the responsibility

that comes with mastery, they are content to let someone else put a roof over their

heads.

That’s the nature of the broad political consensus on how to

deal with the province’s financial state:

they want someone else to do it. Neither of the political parties wants to get

to grips with things. The opposition

parties will snipe, as Sullivan does, but the parties have offered no examples

of spending changes other than increases.

The opposition Conservatives for example criticised Osborne one day for

not having a plan to reduce the deficit and on another day opposed the close of

five schools with very small enrolment, one of them having on three students in

it. Neither of the opposition parties has shown any inclination to

bring down the government, itself a sign of the political agreement that the

government is on the right track.

Premiers resign in January. Will Dwight?

As for

the governing Liberals, they are beset with a malaise common to parties about

to lose a leader or where the leader has become disengaged from his job. Premier Dwight Ball’s office lost three

experienced staff in as many months after the election. He made no changes at all to his cabinet

after the election other than one forced upon him by a scandal. He went through a charade cabinet swearing in

and recently handed out new mandate letters to ministers. The government is frozen in place. It cannot mount a political defence of itself

against even the most feeble of opposition attacks. Against stronger ones, it

is paralysed to the point of silence and inaction.

From a policy standpoint, the government is frozen as

well. There are no new initiatives on

any front, as the recent session of the legislature showed. There appears to be an inexplicable delay in

the relatively routine decision of setting a minimum wage. In perhaps the most glaring example of the

fundamental management problems afflicting the government at the moment, the

finance department and the health department apparently cannot decide which of

the two is responsible for dealing with doctors on their contract talks. Osborne and health minister John Haggie did a

low-rent version of Abbott and Costello the other day trying to figure out who

was on first. They did it in public.

The government has started buying a couple of years of

labour peace by giving the public sector unions salary increases in exchange

for a trivial reduction in government’s long-term liabilities. The largest

public sector has started to cut the legs out from the most vocal employers’

group by mounting a campaign to support local businesses in an economy still

working through the transition from the superheated economy of a few years ago.

By buying off his members in a naked display of political influence, the union

have brought their most ardent critic to heel.

It was not a difficult task.

The other political aspect is federal. Forget what the premiers and ministers from

other provinces say publicly. In private,

other provinces do not treat their whiny kin very well. Ask Danny Williams, who stormed out of a

meeting in the fall of 2004 ostensibly in anger but more likely to avoid a

tongue-lashing from the other premiers who had finally grown tired of the amateurish

scam he was trying to pull. Jason and

Dwight will get the same treatment and the resentment will be even stronger

against premiers from wealthy provinces who have not shouldered the tough

political burden at home like those in, say, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, or

Manitoba.

Frozen at home and feeling a chill across the country, Tom

Osborne will come home to the task of crafting a budget to get his party

through the spring sitting of the legislature.

He might get through this one but Osborne’s fiscal update last week

raises doubts about how much longer Tom or his successor will be able to skate before the ice gives way underneath him.

-srbp-