Justin Simms makes films.

His latest project is a documentary about Danny Williams. Funded by the National Film Board, the movie, imaginatively titled “Danny”, will premiere in Halifax next month at the Atlantic Film Festival.

“We had a window of time,” Simms told The Overcast recently, “where we kind of fought back and stood up to Canada in a way that we never have and possibly never will again.” Simms was talking about the racket a decade ago over federal transfer payments, including Equalization.

Simms said that it was very interesting for the team that made the documentary “to see us, the further we get away from that, reassessing it.”

Williams may be gone from the political scene, but as The Overcast put it, “the rapid pace of change in the province continues. ‘That might make the films and the art we make about the place,’ Simms said, 'all the more important.’”

This film is called a documentary.

By definition, a documentary is not fiction.

It is supposed to be about an aspect of reality, according to one definition. The Oxford dictionary uses these phrases to describe documentary:

- “Using pictures or interviews with people involved in real events to provide a factual report on a particular subject”

- “A film or television or radio programme that provides a factual report on a particular subject.”

Factual.

Fact.

Real events.

Simms’ project is in post-production, meaning they have not only done all the relevant research and writing, but they’ve also shot the thing. They are now piecing it together in final form.

How curious, then, that a film-maker who is just finishing a project that is about real things, actual events, and facts, plainly knows nothing about his subject.

Fought back and stood up “in a way that we never have.”

This is not a dispute about whether the glass is half full or half empty. Simms is plainly unaware of both liquids and objects that hold them. He clearly knows nothing of provincial politics over the past half century, let alone the past decade. So it is that without an understanding of his subject generally and therefore an assessment to use as a starting point, Simms and his colleagues have set about to re-assess it.

Simms appears to have produced a fictional work, not a documentary. Their tale is based on actual people – Williams is real – and actual events – Williams was a popular Premier – but they seem to have put these things together in an entirely fictitious way.

Simms appears to have produced a fictional work, not a documentary. Their tale is based on actual people – Williams is real – and actual events – Williams was a popular Premier – but they seem to have put these things together in an entirely fictitious way.

That is not necessarily a bad thing. A couple of the finest pieces of American film-making in the last century - Citizen Kane and All the king’s men – used actual people and events as the basis for their story.

But if we take Simms’ description of the project, it seems that he and the NFB are about to deliver us something more modern. Think less Willie Stark or Charles Foster Kane (left) and more like Abraham Lincoln: vampire hunter.

But if we take Simms’ description of the project, it seems that he and the NFB are about to deliver us something more modern. Think less Willie Stark or Charles Foster Kane (left) and more like Abraham Lincoln: vampire hunter.

But that is okay.

Fiction presented as fact.

Fantasy presented as reality.

Even without seeing their work, one can conclude that what Simms and his colleagues have done – entirely by accident - is captured the essence of the past decade in provincial politics. Through skillful manipulation of his public image, the active suppression of dissent, and the willing participation of many people through the society, Williams created an illusion of his time in office.

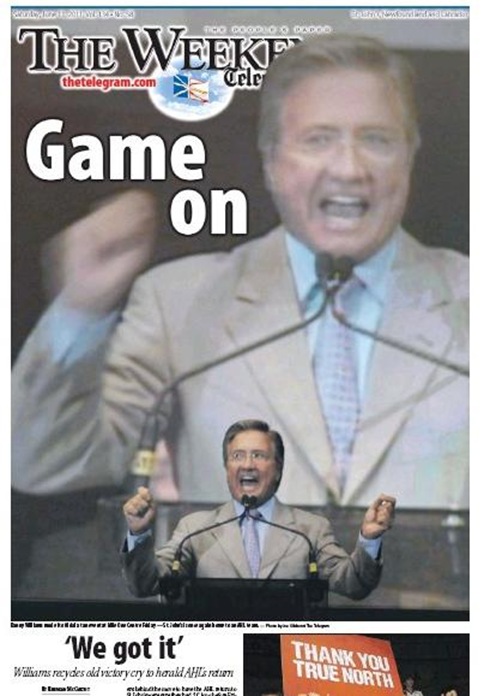

So powerful was the illusion that when he left politics abruptly and unexpectedly, Williams received praise for things he had not done, for things that had not happened yet, and for things other people had done. So powerful was the illusion that apparently now four years after his departure, Williams is the subject of a film whose maker believes in all earnestness that “we” did something that “we never have before.”

The subject is Williams but Simms refers to the individual as if he were the whole. This is precisely how Williams spoke. Williams said: “I believe in my heart and soul that I embody the heart and soul of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians.”

The NFB said that “Williams boosted Newfoundlanders’ self-esteem and the province’s economy.” This is not a re-appraisal. This is Williams own description of his impact offered originally not in 2010 or any time since but in 2006, no less. There is nothing to support the claim Williams did either, unless one adds into the calculation his programme spending more than the province could afford, and yet the studio that practically invented the documentary as an art form can repeat as fact things that are no factual. We are a long way from A little fellow from Gambo or even Waiting for Fidel.

But we are evidently not a long way from Simms’ subject such that he and his colleagues could genuinely appreciate their subject wholly, accurately, and fairly, free of the subject’s own fictional view of what went on. Williams’ illusion is Simms’ illusion, except that this time it is offered up not as contemporary assessment, but as re-assessment a decade later. Repetition does not transform the imaginary into the true.

This is not the first time we have seen someone from the local arts community capture the essence of their political subject inadvertently. We saw the same thing in a video produced by a now-defunct advertising agency in 2008. It took a speech Williams delivered to a party fundraiser and set it to music. Ostensibly, it was in the style of another video based on a speech by Barack Obama.

But where the Obama video used clips of people speaking Obama’s words in their own voices, the Bristol video reduced the people of the province to the status of props, moving their mouths as Williams’ words came out. While Obama’s speech was designed to bring people together in a united effort to bring about fundamental change in their country and in the world, the local video featured one of Williams’ vintage tirades of personal pride and division.

In the speech, Williams is celebrating that the provincial government no longer qualified to received hand-outs from the federal government. He had fought viciously against such a development in 2004 and lost. And in January 2009, a mere two months after his speech, Williams would be complaining bitterly that the government he led would no longer get hand-outs from Ottawa.

It will be interesting to watch Justin Simms’ take on “Danny” if only to see if he even notices that fundamental contradiction. It is the essence of his subject, after all.

-srbp-