There you have proof that even the president of the largest business organization in the province does not understand the first thing about the state of the provincial government’s finances.

Public debt is a really basic idea that you have to know if you want to understand public finance. And you need to understand public finance if you want to have a useful say in how the government is running things. That’s what the folks at the board of trade want to do, one would expect.

And yet Horan got it wrong.

Not a mere technicality.

But dead wrong.

So if the board of trade can bugger up public debt, let’s see if we can walk everyone through the notion in a way that we can all understand.

Debt is a word every adult knows.

It means what one person owes another person that must be repaid. We use the word to cover everything from what happens after someone does you a favour – you owe a debt of gratitude – to the money people borrowed from the bank to buy a house.

Another word you will hear that’s related to debt is liability. For our purpose it means roughly the same thing: something owed by one person - or in this case the provincial government – to someone else. Take the unfunded pension liability, for example. The pension liability is what the government owes it workers when they retire. Normally, a government would put enough money aside today so that, when combined with contributions from the worker, they’d have enough money to pay out down the road when the worker retires. The money would go into a pot and a committee would invest that money so it would make even more money to cover the pensions in the future.

The unfunded liability is – as the name suggests – money the government owes but doesn’t have any cash put aside to cover. It’s not funded. The government has to put the money aside at some point so the unfunded amount is part of the public debt.

To see how much money the provincial government owes, take a look at how the Auditor General described it in his most recent report on the government’s books, the public accounts.

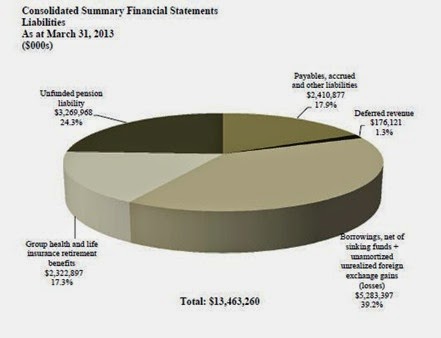

Liabilities represent amounts that are payable or will be required to be paid to third parties and include amounts payable in the normal course of operations, deferred revenue, amounts due to bond holders and other lenders that have provided money to finance the Province’s operations and amounts the Province is responsible for related to employee future benefit obligations. Chart 2 shows the liabilities of the Province as at March 31, 2013.Here’s Chart 2:

Look at that number down the bottom: $13.46 billion. That’s the total of all provincial government liabilities – the pubic debt – counted up the way the accountants keep the books. The unfunded pension liability is listed there as $3.2 billion, or about 25% of the public debt.

Before you get settled, remember that the figures in that picture are 12 months old. In the meantime, the provincial government has added on at least another $5.0 billion for the first round of Muskrat Falls borrowing. We can say the first round because the project isn’t really even started yet. We won’t get the final bills until nearly 2020. By that time, the extra debt load will be about $7.7 billion if the current estimates hold, which, of course, they won’t.

The Net Debt Fallacy

$13.5 plus about $5.0 gives you $18 billion. That’s a pretty big public debt. It’s also a far cry from the debt figure you see people like Sharon Horan or finance minister Charlene Johnson tossing around.

What they are talking about isn’t the public debt, though. It is something the accountants talk about, called “net debt”. They take the liabilities and subtract any cash, bonds, buildings, and the like – called assets – and see what’s left over. As the AG notes, net debt is a commonly accepted way of looking at the financial health of government.

Unfortunately, while lots of people use the net debt calculation to tell them something, it doesn’t tell anyone anything that’s really useful. You see, for a business, net debt tells what you would be left to pay off if you had to shut things down. It gives the people to whom you owe money a sense of how likely they are to get their money back or, to be cynical, how much of a loss they’d take take.

Since we don’t plan on closing down the government any time soon, the very notion of net debt is a bit of a nonsense. Anyone who lends money to government, especially a government in Canada, knows they will inevitably get all their money back with interest.

For the people who have to pay the bills – the taxpayers – net debt doesn’t give them a clue as to the overall financial health of their government. You see, one of the reasons why taxpayers should be concerned about huge government debt is because it takes a huge part of their annual budget just to pay the interest on it. Money that goes to debt servicing, as it is called, is money they don’t have for education, health care, and other things that are infinitely more important than bank profits.

We pay our debts, after all, based on what we owe in total, not the fiction of “net debt”. Look at it this way: you have a house valued at $1.0 million. You took out a mortgage to pay for it of $1.0 million. you don;t have any other debts and you don’t have any other assets and you salary comes in and goes out without any cash left over at the end of the pay period.

Your net debt would be zero, naught, nil. Your assets and your liabilities match exactly. Wonderful stuff. All that debt paid down, as Tom Marshall would have it, and you didn’t lift a finger.

No mortgage payment, then, right? Guess again. You have a lovely mortgage payment every month even though your net debt is nothing at all. If your income just covers all your payments for mortgage, heat, light, groceries, and gas, then you really aren’t very healthy financially even though your net debt is zero.

The provincial government’s debt has been running between $11.0 billion and $13.5 billion for the last decade or so. While the AG stopped listing the liabilities for previous year’s from his annual report, you can find a list - as an example – in the 2011 annual report on the province’s books.

What you can see in the chart on page 446 of the report that year is that the liabilities – the public debt - stayed roughly the same ($13.6 billion in 2007) but the net debt dropped. The only change is in financial assets. A few big cash surpluses gave the government about $5.0 billion in cash just sitting around by 2011.

Tom Marshall and his colleagues like to talk about net debt because it looks like they have reduced how much the taxpayers owe. Tom says the Conservatives “paid down” net debt just like people pay down their personal debts by reducing the actual amount they owe. They can point to the accountants who will say that net debt is a commonly accepted way of judging a government’s health.

When it comes to Muskrat Falls, Tom even said that Muskrat Falls won’t add to the net debt at all. Indeed, it likely won’t. That’s because they plan to label it an asset with a value matching the amount it cost to build it. That’s just like your million dollar home that we talked about earlier.

The Budget Speech

Now you should be able to see why it is wrong to say that the unfunded pension liability is 75% of the public debt. We’ll dig further into the unfunded pension liability in the next post in this Budget Basics series. But for now, let’s just stick with the big numbers and the basic math.

The public debt was $13.5 billion last year. Add on Muskrat Falls and you will take that up to about $18 billion. The unfunded pension liability, as reported by the AG last year was about $3.6 billion.

If you look at the budget speech, though, you can see where the board of trade people screwed up. The finance minister said:

A key component of the province’s net debt relates to unfunded pension and other post-retirement liabilities. Despite an investment of more than $3.6 billion, the liabilities have continued to grow. As of March 31, 2013, they accounted for 67 per cent of net debt. By 2016-17, they will account for 85 per cent of net debt – almost $9 billion.Net debt.

Now that you’ve worked through this post, you should understand the difference between the total public debt and that net debt figure. You won’t be fooled again the provincial government and the board of trade.

That doesn’t mean that the unfunded pension liability and the retirement benefits government owes its employees aren’t an issue. They are.

It’s just that as we get into that topic in the next post in this Budget Basics series, you’ll start to see that what the board and the current provincial government are pushing for isn’t the only solution. Hopefully, we’ll also be able to explain why the pair are focusing on just this one part of what is a very big debt problem that both of them have helped to create.

-srbp-

- The Ongoing Net Debt Fallacy (March 2013)

- Well on the way to debt freedom (April 2013)