If you want to understand what the provincial government’s audited financial statements really mean, you will have to skip Tom Marshall’s comments last week and look instead at the lengthy set of observations from the Auditor General released on Friday.

Paddon’s comments are especially important for two reasons.

First of all, Paddon is the former deputy minister of finance. He knows both the current situation and how the government got there. if he is speaking this plainly now about the government;s financial position, you can imagine what he was saying as the current administration got itself into a mess in the first place.

Second, Paddon explains a great many things in plain enough English so that anyone can understand his points. As you will see, they are not what the government has chosen to talk about.

Let’s start where Paddon starts and walk through the book. You can find more detail in the AG report itself, but let’s pluck out some key bits.

Assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses

Assets: Paddon reports (p.16) that the provincial government had about $5.1 billion in financial assets at the end of March 2013. That included $1.9 billion in cash and temporary investments and $1.8 billion in equity in government businesses.

Paddon explains that these financial assets could be used to discharge liabilities (pay off debts) or to pay for ongoing government operations. That’s certainly true but, in general, there are two big things to keep in mind on this:

- The cash on hand and temporary investments are already ear-marked for spending. For the most part, the cash and temporary investments are just taxes and other money the government collected. The government will spend the money. It just happened to be in the bank the day the auditors did their work. This is a normal feature of annual financial reporting.

- The equity is a theoretical amount that reflects the auditor’s best estimate of what government could get if they sold off the liquor corporation, for example. If a government tried to sell it, they could get more or they could get less. But what government in Newfoundland and Labrador is likely to sell off any government business, even if they desperately needed it?

The government had about $3.9 billion (p. 18) in what the auditors call non-financial assets. These are things like buildings. They have a value. Again, if you had to, you could sell them off to pay the bills. Theoretically. Not likely, unless things went completely to pot and even then it would be unlikely.

For those reasons, your humble e-scribbler doesn’t tend to pay much attention to the assets part of the annual statements except to note they are there. The big problem with this part of the financial statements is that the assets get used to come up with “net debt”. It’s a perfectly simple idea: liabilities, less assets. The problem comes when politicians take the auditor’s concept of “net debt” and start tossing it around like it actually meant they had reduce public debt when they hadn’t.

Liabilities: Rather than talk about net debt, pay attention to liabilities (p.17) instead. This is the stuff you will pay now or in the future.

$13.5 billion. That’s made up of:

- $5.3 billion in borrowings,

- $3.3 billion in unfunded pension liability,

- $2.3 billion in group life and pension benefits for government employees,

- $2.4 billion in money owed to other people and not yet paid, as well as other liabilities, and

- around $176 million in money the government is due but hasn’t collected yet.

Revenue: $7.5 billion in the year that ended on 31 March 2013. (p.20) $3.5 billion in taxation of all kinds, $1.8 billion in offshore royalties, $992 million from the federal government and the rest in a mix of other types of income.

Expenses: $7.7 billion. (p.21) Social sector – health, education, justice etc) – cost $4.3 billion. Government operations and the legislature cost $1.8 billion. The resource sector of government cost about $1.5 billion.

Financial Condition of the Province (Chapter 5)

Nominal and Real GDP: Nominal GDP is the value of goods and services produced in the province at market prices. You can see the impact of price changes – oil going up and down for example – in looking at nominal GDP. Real GDP is shown using a particular year as a base (numbers shown in the value of 2007 dollars, for example). That shows the changes in actual production in the economy.

Paddon includes a table on page 24 that shows actual nominal and real GDP from 2007 to 2012 and forecast from 2013 to 2015.

Surplus and Deficit (p. 25):

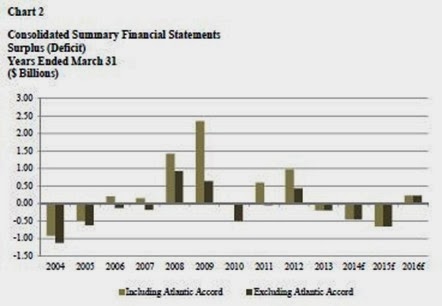

“Consistent with the economic growth over the past ten years, the Province has also recorded surpluses in six of the past ten years (Chart 2) and its ability to raise revenue and support debt has improved during this period.

However, the surpluses that the Province has experienced in recent years have primarily been the result of increased offshore royalties and payments received from the Federal Government under the Atlantic Accord Agreements. The amount of revenue received from offshore royalties is dependent upon world oil prices and/or production levels. World oil prices are highly volatile and production levels relating to non-renewable resources can vary significantly. Changes in these factors can result in significant variability in revenue from year to year.” [Emphasis added]

Paddon includes this chart showing the annual surplus or deficit. The light colour shows the amount including the Atlantic Accord (1985) payments. The dark line shows what the deficit or surplus would have looked like without it.

Paddon’s chart is misleading because it continues to show the impact of the 1985 money even though it stopped in 2012. But, if you look at the years before then, you can see that the Conservatives haven;t been very good at financial management without the help of handouts from Ottawa and windfalls in 2008 and 2009 that came entirely from global oil prices.

Debt Sustainability: Paddon makes a couple of comparisons of net debt to government revenue (pp.31-33) that reinforce the idea that government’s debt load isn’t sustainable.

Pension liability and life and health benefits: Given that they total $5.6 billion of government’s $13.5 billion liabilities Paddon devotes considerable attention to how the size of that liability has grown. (pp. 35-41)

Take a look at page 39, though and you’ll see Paddon’s succinct list of three reasons why the employee benefits liability has grown.

The first reason is volatility in the marketplace. The government has a pension investment fund. The money from the fund will help to pay the pensions in the future. Some years, the investments don’t do as well as others. As a result, the government winds up looking like it will have to pay more than it looked like it did the year before.

Note the words “looking like”. That’s because we are not talking about actual liabilities with specific amounts. We are taking about what will happen in the future if things stay the way they are now. The thing is, they won’t. If the investments do well, then things change: government has more assets.

The second reason for the growth in liabilities is that we have lots of people working and therefore earning those benefits. Pretty simple.

The third reason for the growth in the liabilities is the interest on the part we don’t have money put aside to pay. Again, that seems pretty simple.

There are actually two more reasons for the growth in the liability for benefits, but Paddon’s report doesn’t put it that way. Part of the increase is due to the way the accountant’s want to report things now compared to the way they used to report it. Another reason for the increase is the difference between the actual experience and what someone forecast it would be however many years ago.

Those two reasons are bit more nebulous than changes in the marketplace value of shares that government could sell to raise cash to pay the pension benefit, for example. They don’t diminish the seriousness of the overall issue but they do give us a reason to think carefully before we make any decisions about how to handle the pension and benefits problem.

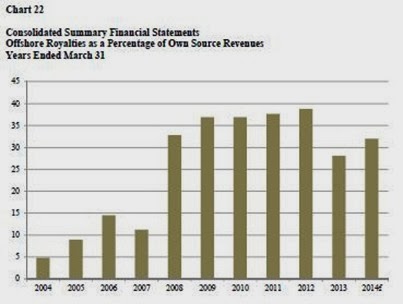

Oil Revenues (pp. 44-47) Given the impact oil money has on government spending, Paddon spends a considerable chunk of his report walking through changes in oil revenue over time, monthly oil production, and all sorts of other details.

Paddon offers a familiar caution (p.44):

Given its lack of control over the factors that impact oil royalties, and its increasing reliance on this revenue source, Government has to carefully consider the degree to which it relies on this revenue source to fund its programs and services in the future.

On page 52, Paddon includes a chart that shows the share oil is of the provincial government’s own-source revenues.

Per capita expense (p. 57): The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador spends 40% more per person than the average of all the other provinces to deliver its public services.

In order to get per capita spending down to the national average the government would have to cut spending by $2.3 billion.

Debt expenses (p. 60) The provincial government could save $186 million a year if it reduced the cost of servicing the public debt down to the national average.

Tangible capital assets (p. 62): Government is very proud of its capital works spending.

The acquisition of tangible capital assets may be seen as a means to provide better services and reduce future expenditures. However, the acquisition of tangible capital assets increases Net Debt as the tangible capital assets have to be acquired through either the use of financial assets or the assumption of additional liabilities.

During the next two years, Government expects to incur deficits from its operations, which will increase Net Debt. The acquisition of tangible capital assets also increases Net Debt. Therefore, Government will need to carefully consider whether the level of tangible capital asset acquisitions that has occurred in recent years is sustainable in the future.

Demographics (pp. 64-68): Regular SRBP readers will find this bit of Paddon’s report familiar.

- “Population shifts between various regions of the Province can create significant challenges for Government and have to be given serious consideration when determining how to deliver public services in a cost effective and efficient manner. This is particularly important when planning for the development of infrastructure including roads and health care and education facilities. Government may find it increasingly challenging to maintain the delivery of public services, such as education, in regions where there are declining populations. This is in contrast to other regions where Government may struggle to keep up with the demands for education services that are created by increasing populations.” (p.65)

- “As the population ages, there will be an increased demand for certain public services such as health care and seniors’ housing.” (p.66)

- “In addition, aging of the population will likely be more prevalent in certain regions of the Province, as younger people move to larger centers to pursue educational or employment opportunities. This may have significant

implications for long term planning of regional health care facilities and service delivery models.” (p.67)

-srbp-