Flip over to the Occupy NL blog and you’ll see a critique of some recent SRBP posts on the provincial government’s bonus cash for live babies program.

Let’s summarise the critique and then go from there. While this summary will get you through this post, to be fair and to make sure that nothing gets missed, go read the full post with all the charts included at Occupy NL.

The author takes issue with the SRBP approach in the initial post in the December series, which looked at the total number of births. He contends that we should look at “the average number of live births a woman can expect in her lifetime based on age-specific fertility rates in a given year. Secondly, his analysis doesn't acknowledge that declining birth rates is a trend nation-wide and that provincial rates should be compared to what is happening in other provinces.”

The author concludes, in part:

The jump happened in 2008, the year after the new policy was enacted. Moreover, the difference has actually narrowed since then. Now I'm sure that the booming economy has a lot to do with this, but the data is entirely consistent with the PC baby bonus having a significant and enduring effect.

Okay.

“We can’t be a dying race.”

The 2007 Conservative policy was aimed at reversing the declining native-born population in the province. As CBC quoted then-Premier Danny Williams when he announced the policy:

"We can't be in a situation where our population is shrinking, where we have more people dying than are being born."

That sets the context pretty clearly. The problem is the declining population. The policy solution is to offer a single payment for live births (or adoptions) as well a small amount of cash per month for the first year after birth.

In that context, taking a look at the total number of births is pretty much the only basis for assessing the success or failure of the policy. If the number of births went up in 2008 (the year after the policy) and continued to rise afterward or even held at the level achieved in 2008, then we could consider the policy was working.

A quick look at the available figures suggests that this isn’t the case. SRBP used CANSIM table 053-0001 as the source for this chart.

While there is a pronounced spike upward in 2008, the general trend over the next four years is downward. The total number of babies born in Q1 2012 is higher than it was at the early part of the decade, but the trend is downward.

On that basis, the 2007 government policy is a bust if it was aimed at increasing the provincial population. The number of babies born may have gone up in 2008, but it is going downward again afterward.

Replacement

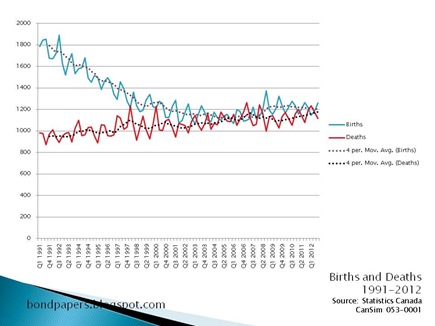

take another perspective: look at deaths and births. The next chart is deaths (red) and births (blue) over the past two decades, by quarter. We’ve added in a trend line showing the rolling four quarter average.

To the left, we see the number of deaths well below the number of births. But, the number of deaths continues to trend upward and except for the period from about 2004 to 2008 when the births were roughly stable and then jumped upward, the trend for the number of births continues downward.

Newfoundland and Labrador has the highest average age of the population of all the provinces in Canada. To get a sense of what the trending on these two lines might look like have a gander at the population pyramids contained in a 2007 assessment by the provincial finance department.

The light coloured segments represent the baby boomers. Look at the bars below those light ones to get a sense of the population of child-bearing age coming along in the years immediately ahead.

Uh huh. As you slide those numbers along, the baby boomers are going to shuffle off this mortal coil at a higher rate than the babies are likely to come along.

That is, unless the number of babies per woman goes up dramatically.

Fertility Rates

That brings us to the Occupy NL observations. Fertility rates in Newfoundland and Labrador have “increased relative to Canadian averages for women of all ages…”.

Here’s the comparison for the 20 somethings, using data from CANSIM 102-4505. On the legend, the top lines are Canada and the bottom lines are Newfoundland and Labrador.

For the 20-somethings between 20 and 24 (the lower pair of lines), the Canadian trend is downward. The Newfoundland and Labrador rate (births per 1,000 females) changed from a downward trend to an upward one around 2005 – two years before the policy announcement - peaked in 2008 and has been on the way downward again since then.

For the 20-somethings between 25 and 29, the Newfoundland and Labrador rate started to increase the year before the provincial government announced the policy.

Solid lines are Canada. Dashed lines are Newfoundland and Labrador Top two lines are the 30-34 age cohort. Bottom two lines are for the 35-39s.

The Newfoundland and Labrador numbers match the general increase in the national figures, although the actual rates are lower. Notice, though, that the upward trend comes at least seven years before the provincial government policy.

While you can argue that the 30-34s increased at a slightly higher rate after 2007, the best you can get out of that is a correlation between the rate of change and the government policy. There are other plausible explanations for the increase, including the increase in population generally of people of child bearing age during that period as a result of in-migration.

So far, there is no indication that the government policy had any impact on fertility rates other than to possibly induce a one year increase in the existing trend.

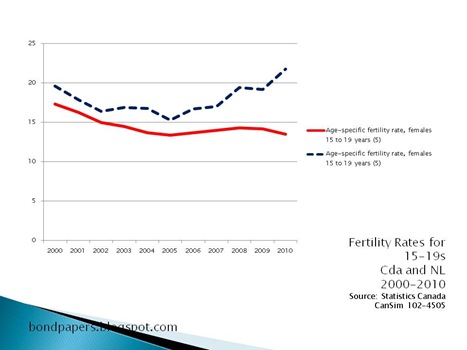

We could keep going with this but as a last chart, let’s look at the 15-19s. Solid red line is Canada. Dashed blue line is Newfoundland and Labrador.

The fertility rate in Newfoundland and Labrador among 15 to 19 year old females is definitely increasing but note that, once again, it predates the government pro-natal policy by at least two years.

What a Shock

None of this is surprising. Birth rates have been declining in the developed world for decades. According to a 2007 policy brief by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development the rate is below that needed to maintain the existing population.

What’s more, the OECD brief also notes what is fairly obvious from the numbers implicit in the population pyramid: a smaller population would have to crank out babies at a significantly higher rate just to keep pace with the existing population, let alone cause a population increase.

A 2010 RAND Corporation study of experience in Europe showed similar declines in fertility to those documented by the OECD. RAND concluded that:

No single policy intervention has worked to reverse low fertility. Historically, governments have attempted to boost fertility through a mix of policies and programmes. For example, France in recent decades has employed a suite of policies intended to achieve two goals: reconciling family life with work and reversing declining fertility. To accomplish the first goal, for example, France instituted generous child-care subsidies. To accomplish the second, families have been rewarded for having at least three children.

Sweden, by contrast, reversed the fertility declines it experienced in the 1970s through a different mix of policies, none of which specifically had the objective of raising fertility. Its parental work policies during the 1980s allowed many women to raise children while remaining in the workforce. The mechanisms for doing so were flexible work schedules, quality child care, and extensive parental leave on reasonable economic terms.

Newfoundland and Labrador’s 2007 baby bonus policy has proven to be a failure. The policy failed - as a government policy - because it took a simplistic approach to a complex problem.

-srbp-