Effective public policy must be based on a clear understanding of the problem and its relation to other issues, as well as public needs and behaviour."...almost 50% of all wind borne litter escaping from landfills in Newfoundland and Labrador is plastic, much of it single-use plastic bags....

There's the problem, defined neatly.

The quote is from Municipalities Newfoundland and Labrador's campaign against plastic shopping bags.

Put the quote in a search engine on the Internet and you will turn up all sorts of places, including news stories, that use that phrase or a slight variation on it in coverage of the popular campaign to ban plastic bags from the province. Here's an example from The Telegram in 2017 and another a couple of days later that went province-wide.

One small question: what's the source for the statistic?

Small Question. No Answer. Big problem.

It's a small question - a simple one - but when it comes to any decision to fix a problem, it's a very big answer. We should be clear on what the problem is. Once we know what the problem is, we can pick the best way to address the problem.

That's public policy in a nutshell: fixing problems.

And that's the policy process in a nutshell:

- Identify problem.

- Identify best solution.

- Implement best solution.

So if we can say that wind-borne plastic is half of our litter problem - within the bigger problem area called waste management - and that we are talking shopping bags, well, it is obvious that a ban on plastic bags knocks out half our litter problem right there.

Boom. Problem defined, solution found, only a matter of doing it.

No-brainer, as St. John's deputy mayor Sheilagh O'Leary said in 2017.

It is not just about litter. The bags get into the water and kill wildlife there. Plus they are made of plastic, which is made from oil, so reducing plastics consumption would be an important part of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the destruction of our natural environment through exploration for hydrocarbons, and the spillage of them in small or enormous quantities.

No brainer. Simple. Easy. Ban plastic shopping bags.

Ok.

So where's that local data on wind-borne litter, then?

How about some data on litter generally?

MNL doesn't give any information about where it got the idea plastic bags were such a big litter issue. There's nothing on its website, whether it's in the current material, linked above, or even in a 2017 MNL news release that got all that media attention in 2017.

A 2018 document from the provincial municipal affairs and environment department that specifically described plastic bag "management" doesn't use the statistic MNL cited.

The only place where there's a comment generally like it for Newfoundland and Labrador is in the notes from a meeting of waste management officials in September 2018. A couple of guys from western Newfoundland are quoted in "Options management of single-use plastic items" saying that "the majority" of their wind-blown litter problem is from plastic bags.

Not really a solid quote.

More like hyperbole or a rough guesstimate.

And it is *after* the date when MNL used it.

A 2005 assessment for the Scottish government's proposed plastic bag levy compared carrier bag alternatives for some environmental impacts (left). It used a particular type of plastic bag that is easy to recycle as the baseline. The report confirms the observation about the amount of water needed to produce paper versus plastic. It also showed that some carrier bag alternatives needed to be used multiple times to match the single-use bag made of high density polyethylene.

A 2005 assessment for the Scottish government's proposed plastic bag levy compared carrier bag alternatives for some environmental impacts (left). It used a particular type of plastic bag that is easy to recycle as the baseline. The report confirms the observation about the amount of water needed to produce paper versus plastic. It also showed that some carrier bag alternatives needed to be used multiple times to match the single-use bag made of high density polyethylene.

Taylor found that while the ban did reduce plastic carrier bag usage by 40 million pounds a year, there was a corresponding 12 million pound increase in trash bag sales.

Taylor found that while the ban did reduce plastic carrier bag usage by 40 million pounds a year, there was a corresponding 12 million pound increase in trash bag sales.

Not really a solid quote.

More like hyperbole or a rough guesstimate.

And it is *after* the date when MNL used it.

So, not really good enough.

And it's not really good enough when the official figure from the municipal affairs and environment (MAE) department puts the bag's share of litter at a mere six percent.

According to MAE's February 2018 survey of the plastic bag issue and potential options for addressing it, The Multi-Materials Stewardship Board "completed roadside litter audits of

231 sections of road in the province [in July, 2016]. In all, 5,453 pieces of large, visible

litter (greater than one inch square) were found during these audits. Of this

large litter, roughly six per cent comprised of single-use plastic shopping

bags, while take-out cups, their lids and straws, made up over 16 per cent (the

second highest category behind other litter)." [emphasis added]

But the idea *is* popular.

In mid-February, municipal affairs minister Graham Letto said plastic bags are not the number one polluter, but the move is popular. Around the same time, VOCM asked its listeners whether they supported a ban on bags. Over 3300 people responded to the unscientific online survey and 74% said to go ahead an ban the bags.

Not a simple as it looks

There are a few other details left out of the current popular discussion of plastic bags and banning.

For one thing, the most successful examples of places that reduced plastic bag use - Ireland and Denmark - didn't ban anything.

Plastic bags produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions and use less water and chemicals in their production than cotton or paper alternatives, according to University of Oregon chemistry professor David Tyler.

"Cotton is typically grown on semiarid land so it consumes a

huge amount of water, " said Tyler, "and you also need a lot of pesticides. About 25 percent of

the pesticides used in this country are used on cotton. Paper is just typically

considered a fairly polluting [sic] industry. Whereas the petroleum industry, where

we get our plastics, doesn’t waste anything. Chemists have had sixty to seventy

years to make the production of plastics fairly efficient and so typically

there is not a lot of waste in the petroleum industry."

A 2005 assessment for the Scottish government's proposed plastic bag levy compared carrier bag alternatives for some environmental impacts (left). It used a particular type of plastic bag that is easy to recycle as the baseline. The report confirms the observation about the amount of water needed to produce paper versus plastic. It also showed that some carrier bag alternatives needed to be used multiple times to match the single-use bag made of high density polyethylene.

A 2005 assessment for the Scottish government's proposed plastic bag levy compared carrier bag alternatives for some environmental impacts (left). It used a particular type of plastic bag that is easy to recycle as the baseline. The report confirms the observation about the amount of water needed to produce paper versus plastic. It also showed that some carrier bag alternatives needed to be used multiple times to match the single-use bag made of high density polyethylene.

A 2006 report for the United Kingdom's environment agency reached similar conclusions in its assessment of the life-cycle of supermarket carrier bags.

Just as it isn't clear that plastic bags are the pure evil some describe, banning is not an effective solution to the problems that plastic bags do pose for litter, landfills, and waste processing.

Balloon-squeezing

Rebecca Taylor is an American-born economist now lecturing at the University of Sydney in Australia. Her most recent research - the full paper is here - looked at the impact of plastic bag bans in California. Taylor notes that California is the first state to adopt a state-wide ban on plastic bags in 2016 after a series of local measures came into effect in municipalities across California between 2007 and 2015. That makes it a good example of how the policy of banning has worked since there is plenty of data readily available.

Taylor found that while the ban did reduce plastic carrier bag usage by 40 million pounds a year, there was a corresponding 12 million pound increase in trash bag sales.

Taylor found that while the ban did reduce plastic carrier bag usage by 40 million pounds a year, there was a corresponding 12 million pound increase in trash bag sales.

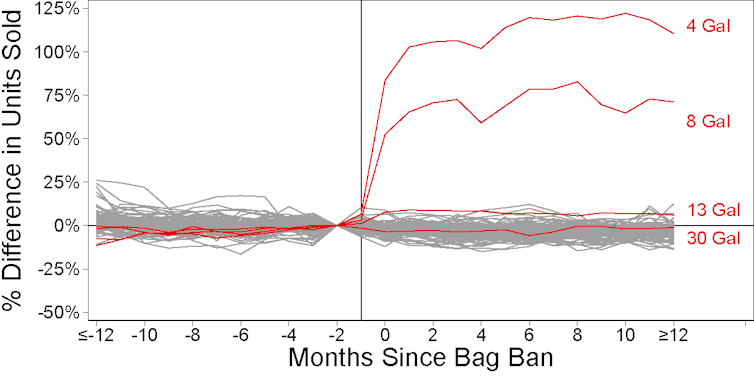

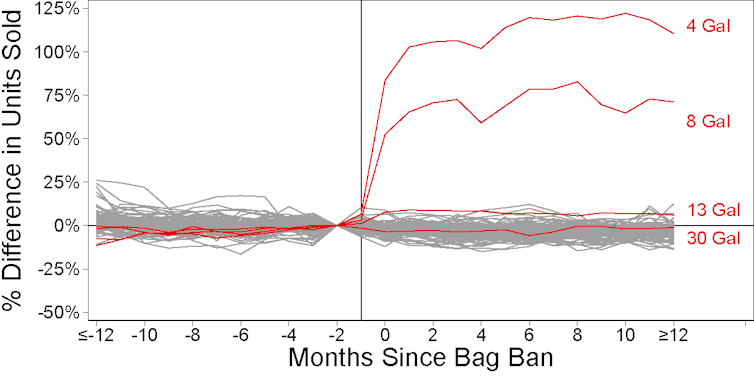

In other words, "30 percent of the plastic eliminated by the ban was coming back in the form of

trash bags, which are thicker than typical plastic carryout bags." Sales of four gallon trash bags increased by 120%, while sales of eight gallon bags jumped by 64%.

Taylor also found that people who tended to recycle shopping bags - the folks who purchased plastic garbage bags instead - tended to have children under five years of age, own a dog or cat, were frugal, and/or were better educated. Recycling of carrier bags itself, prior to the state-wide ban actually reduced the production of new carrier bags by between 12 and 22 percent, according to Taylor

Better ideas from Ireland and Denmark

As Taylor notes, policies don't work when policy makers don't understand the issue or fail to anticipate how the public will behave in new circumstances. Since using plastic bags is not free of environmental consequences, Taylor recommends alternative approaches to a simplistic ban based on the experience in California in order to achieve the policy goal of reducing the use of plastic shopping bags.

"One option would be to offer incentives for producing

inexpensive, thin carryout bags specifically designed and marketed to be used

first as carryout bags, then for trash. Such bags would need to sell for less

than 9 cents per bag to be price-competitive with current 4-gallon trash bags.

Ideally, they would be thin enough to contribute no more to climate change than

traditional carryout bags."

While that isn't necessarily an option in Newfoundland and Labrador's small market, another of Taylor's ideas is viable. She recommends a fee on each bag, as adopted in Washington, DC and very successfully implemented in Denmark and Ireland.

Since fees, taxes, and levies on carrier bags don't address all the issues associated with switching from plastic bags, Taylor suggests that the tax approach "could be improved by educating customers about the environmental

benefits of reusing disposable products. As a general rule, the more an object

can be reused – even a disposable item – the better for the environment."

Effective policy is more than a fad

Effective public policy must be based on a clear understanding of the problem and its relation to other issues, as well as public needs and behaviour. In Newfoundland and Labrador, we have the experience of how policies that were superficially popular produced disastrous, costly, and far-reaching consequences.

Policy fads are like anything that is hyped, whether it is a celebrity or a fashion. Once the heat wears off, you are left with a bunch of hoolah hoops, pet rocks, and Milli Vanilli albums.

In the case of banning plastic shopping bags, we appear to have a superficially popular idea that doesn't appear to be based on evidence and experience in other jurisdictions. We know what works elsewhere. Banning bags doesn't work.

Bag bans also don't address the waste management and litter problems in our own province since it is limited to one small item and ignores other sources of waste. Plastic bottles, coffee cups and lids, cigarette filters, straws and other waste associated with fast food are more prevalent than shopping bags, based on a study by MMSB and reported by Cowan.

MMSB's province-wide clean-ip turned up 924,000 litter items from Tim Horton's alone in the form of paper coffee cups and paper food bags. The second most prevalent litter brand was McDonalds, with Pepsi coming third, and Canadian Classics cigarettes coming fourth. Goudie pointed out that 60% of municipalities in the province don't offer public waste bins for residents to use.

Fortunately, we also have the experience in both smoking reduction and recycling and waste management that shows how effectively a well-developed and implemented policy can change public behaviour by changing attitudes. It takes more than one single measure to produce the desired result. But with a solid understanding of both the problem and the solutions, you can produce dramatic changes.

What we also know from those experiences of the 1990s is that success in the long-term requires renewed and refreshed effort, not the adoption of simplistic ideas no matter how popular they might be.

-srbp-