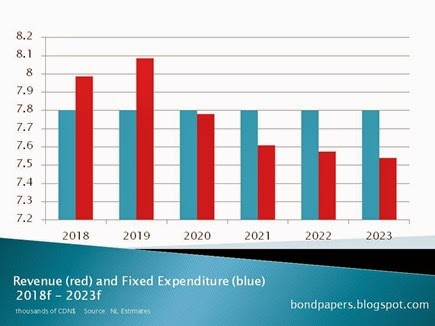

This pretty picture shows a very ugly problem.

All that space in between those two lines is debt. It is either borrowing from the banks and other lenders or it is borrowing from ourselves through spending all our one-time oil money. If the government spends as they indicated in the budget, about two thirds of that gap on the far right is borrowing from the banks. One third is from oil money.

Just for a bit of fun, let’s project ahead into the future a bit to see what might happen. We’ll use the oil price projections the government used. And we’ll use the most recent oil production figures from the offshore board. You might be surprised at the results.

What we are going to do here is see what we have to do in order to get a surplus. We need a surplus if we want to pay down debt and/or put some money away for a rainy day.

Everything up by two percent (except oil)

For the first chart, let’s assume that both spending and non-oil income go up by two percent each year. That basically keeps place with inflation. For our oil income, we’ll use the forecast price of US$90 a barrel. Production follows the offshore board forecast

There’s no surplus. Ever. This is the most optimistic set of numbers you can get using all the current thinking. It even allows for growth in non-oil revenue, something we haven’t seen since 2008. On the spending side, it allows for a modest growth in spending just to keep pace with inflation.

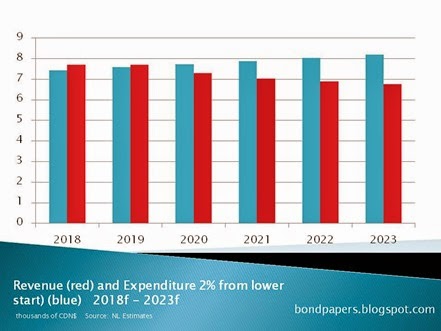

Fixed Expenditure

In the second chart, let’s hold spending constant at $7.8 billion. That would be an actual drop in spending of two percent a year. It’s complete unrealistic, politically, but let’s assume that anyway. We are also assuming here a two percent increase every year in non-oil income. That’s also completely unrealistic given recent experience.

Poof.

We get a couple of decent surpluses in the two peak years of oil production. Then it’s right back to deficits again. They mount rapidly as oil production drops off.

Not good.

Let’s try a third set of numbers. In this one, we hold the spending not at the budget forecast number but at roughly where government has held spending for the past couple of years. It won’t be realistic politically, but let’s give it a try anyway.

Present trends continue

What we basically do is hold spending at $7.0 billion. We’ll also hold non-oil money at $4.6 billion and vary the oil spending based on forecast production and US$90 a barrel.

Here we get much smaller surpluses in those two peak years at the beginning. Then it’s right back to deficit again.

On both the expenditure and revenue sides, this one most closely approximates what has been happening for the past few years. In order to get to this sort of scenario, you’d have to hold spending under tight control. Essentially, you’d be going back to the way the provincial government used to manage public finances before the current crop of people laughingly called conservatives got their hands on things.

In this scenario, the accumulated deficits for the period after 2019 add up to about $6.0 billion. For an extra twist, let’s assume an increased price for oil of $80 and $85 dollars a barrel in the two years before our scenario above with $90-a-barrel oil.

You can see that the scenario there looks a lot like the one the provincial government allowed. The deficit shrinks as we hold spending under control and let revenue rise to meet it. The problem for the current government forecast is that it cuts off at the point surpluses return. Extend the thinking a bit further and you see that the deficits come back pretty quickly..

Change the assumptions…

Like all of these scenarios, they live and die based on the assumptions. Oil could be higher than the assumed price. It could also be much lower. The purpose here isn;t to say what will happen.

What these scenarios should illustrate is how difficult it would be for the government to return the budgeting to surplus. Even in what we might today consider optimistic conditions – lots of oil and a price about $25 to $30 above current – the government would have to clamp down on spending to a degree that would be very difficult politically.

Just reduce those assumptions about the price of oil. Even with a couple of years of big oil production of about 115 million barrels each year, a surplus would be very hard to attain. That’s an affirmation of just how far out of whack government spending has been for the past six years.

-srbp-