Don Mills says people in Newfoundland and Labrador have a false impression of the state of the provincial economy.

Wade Locke says Mills is full of it.

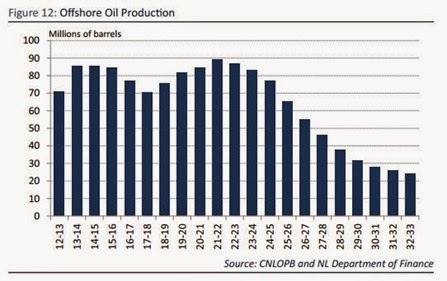

One of them included a slide showing projected offshore oil production. (right)

Locke is just plain wrong

Wade’s slide is not as clear as the original used by the offshore regulatory board. Take a look at that one.

Locke’s entire argument is built around oil. The text under the graphic above reads like this:

After 2015‐16, production is expected to increase. If other projects come on stream (like Bay d’Nord), NL can expect production to be at or above current level for the next 15 to 20 years, at least. Oil prices are increasing currently and are expected to pick up further in the near future.

Everything will be okay because oil is coming back. In another part of his presentation, Locke says emphatically that “We have yet to hit peak oil.”

That’s just not true. What you can see plainly from the CBNLOPB forecast is that not only have we hit the peak already, but the forecast spike in one year’s due to come production is actually going to be the third highest. The first two are gone.

After you have looked at the peak, look at the years immediately afterward. What you can see there is that, even with Hebron, oil production offshore is forecast to decline rapidly. In the five years between 2023 and 2038, oil is forecast to drop by half, from about 80 million barrels a year to 40 million.

Wade’s claim about 15 to 20 years of wonderful oil production is based entirely on the gigantic “if” about other fields. Those fields are, at best, years away from development and production. When they come on stream, those fields will simply replace the earlier fields as they dry up.

Add money to the mix

To get a sense of what government will have to deal with, consider that this year the government will have to borrow $2.1 billion to balance the books. Government has increased spending by 12%. The 2015 budget forecasts continued deficits until around 2020.

The government is heavily dependent on oil spending thanks in large measure to the sort of advice Locke has been offering. There are no plans currently to do anything with government spending but wait for the oil to come back.

The budget forecast is that oil will be about $90 a barrel by the end of the decade. That’s basically how they forecast a surplus and how they can justify doing nothing in the meantime but borrowing more money.

Goldman Sachs lowered its five-year forecast for Brent crude this week. Between 2016 and 2019, the company is forecasting prices at between US$60 and US$65 a barrel. In 2020, they expect it to be US$55. That’s considerably lower than the provincial budget estimate. And to be sure, the budget estimate was also about US$20 a barrel higher than Goldman Sachs previous

Let’s estimate government royalties in the peak period of oil production to come. We’ll use the CNLOPB numbers, taken from the chart. We’ll also use three estimated oil prices. We’ll call the government estimate of US$90 a barrel our high case. We’ll take a number below the Goldman Sachs estimate as our low case (US$50). And in the middle we’ll use US$70 a barrel.

Multiply the price per barrel by the output and you get total revenue. Take 30% of that and call it the provincial royalty. That’s roughly what it should be. And if it’s off by a measure, it;s close enough for the purpose of our estimate.

At the assumed high price, things are wonderful in the first two years. $3.1 billion would be more money than the government has ever earned from oil in any one year. It still wouldn’t equal the combination of oil (1.15 billion) and borrowing ($2.1 billion) in 2015, though.

And if that’s the result at the high estimated oil price, everything less than that would be…well… less than that. Look at it this way: hold the current budget exactly as it is and drop it down in 2020. Based on this price of oil, the government would still have to borrow money to make ends meet.

The problem the government would face after 2023 is basically exactly the same problem that it has been having for the past three or four years. Oil prices have to keep climbing as oil production declines just to balance the books. That doesn’t allow for any increase in spending at all.

It also doesn’t allow anyone to put aside any money in some kind of heritage fund. That ship has basically sailed.

A worse case scenario

Now that you’ve had some fun with that, consider the CNLOPB production forecast in 2013. You can find it in a document that accompanied the provincial government’s budget for 2013.

The peaks in this forecast aren’t as high as the ones in the 2014 forecast. What you will see, though, is that the drop-off through 2020 and 2030 is about the same in both forecasts. The main difference is that the peak is higher in the 2014 forecast and happens three years earlier than in the 2013 forecast.

Now apply the three price assumptions.

The peak in this scenario comes in 2021. Even at the peak production, and with the high oil price forecast, provincial oil royalties only hit about $2.4 billion. If we copied the current budget whole and transposed it to 2021, the government would still have a deficit of about $800 million. They’d also have been running deficits larger than the current budget forecasts.

In the low price scenario, things are much worse. Oil revenue peaks at about $200 million more than it will be this year.

-srbp-