Lots of people like the idea of free tuition at post-secondary institutions like Memorial University or the College of the North Atlantic.

In the recent provincial general election, the provincial New Democrats included it as one of their major policy ideas.

A Memorial University engineering professor took up the argument last week in a letter to the editor at the Telegram:

By not having free tuition at MUN, we are basically discriminating against poor people and the middle class.

That’s one of the popular misconceptions about access to higher education. People think it’s about cost and that people who have less money can’t afford to attend.

Research like the studies mentioned in earlier posts don’t back up the popular belief. A recent study of experience in Ireland, for example, found that the “only obvious effect of the policy was to provide a windfall gain to middle-class parents who no longer had to pay fees. [p. 14]”.

What worked against people from low income and middle income families – according to other studies – was academic achievement in grade schools.

Tough luck for them. The same engineering prof who wants free tuition also wants to toughen the entrance stands:

Because not everyone can handle the workload at a university, to be eligible for free tuition a student would need a high school average greater than, say, 80 per cent.

To keep it, a student would have to maintain that average at MUN.

The inevitable result of that policy - free tuition coupled with tough academic entry standards - would be to further skew the benefit of free tuition to those who don’t actually need the leg up in the first place.

The usual alternative to free tuition is an approach that targets financial assistance at specific groups. In his 2005 review of the Ontario post-secondary system, Bob Rae recommended – among other things – that the provincial government provide improved grants, adjust the student loans program and promote scholarships and similar financial support for students who qualify on economic grounds.

Inevitably, though, these approaches rely on government funding of university and college education. The only difference is how much the government will pay out of general revenues at the front end.

Government subsidised education has one feature that people often don’t consider. Subsidy. That’s what it is, by the way, whether you talk about free tuition or the sort of approach in Newfoundland and Labrador today. The only difference is whether the subsidy is 100%, as in the free scenario, or some other percentage.

Subsidised education puts the focus of discussion about education costs to the students rather than the education itself. The alternative – like in the American approach – values the education. Universities set tuition as a source of income. The level of tuition can reflect the cost of delivering the education plus any premium for the type of degree or the institution itself.

One alternative that blends the two approaches together is the graduate tax. In its simplest form, tuition costs can be set based on the cost of delivering the education or a market calculation of of what the degree or diploma is worth.

The student does not pay while attending college or university. After graduation, the student pays a percentage as an additional tax on income for a fixed period of time.

Such an approach has one significant advantage over the current Canadian model or any of the variations some have proposed: it eliminates the regressive nature of the policy that sees the entire society providing a benefit to specific individuals at a partial or near complete discount.

With a graduate tax, the beneficiary of the education winds up paying for it. What’s more the beneficiary pays based on the value of the education itself as reflected in post-graduate employment.

None of that addresses the accessibility issue for university, but at least it holds out the prospect of creating a post-secondary education system that is fairer than the one that currently exists in Newfoundland and Labrador.

- srbp -

.

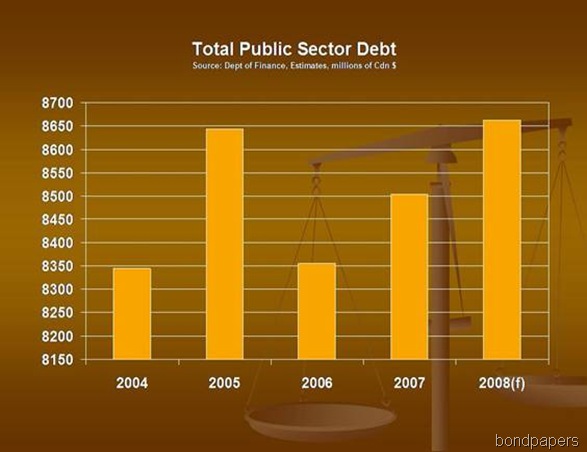

1. Reduce the public debt by 50% within 10 years. Beginning in the early 1990s, successive administrations restructured public borrowings to convert debt held in foreign currency. As a result, the current burden on the treasury is significantly reduced and uncertainty due to currency fluctuations has been all but eliminated.

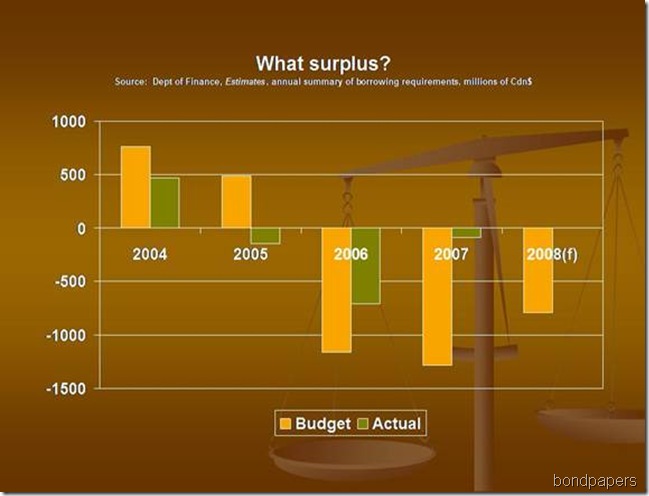

1. Reduce the public debt by 50% within 10 years. Beginning in the early 1990s, successive administrations restructured public borrowings to convert debt held in foreign currency. As a result, the current burden on the treasury is significantly reduced and uncertainty due to currency fluctuations has been all but eliminated.  2. Balance the books, every year. Government surpluses in recent years have been built on the blind good fortune of astronomical oil prices. Those prices are an unreliable source of cash. On a cash basis, the provincial government has actually been in debt each year since 2005. That means new borrowing to add to the burden of public debt.

2. Balance the books, every year. Government surpluses in recent years have been built on the blind good fortune of astronomical oil prices. Those prices are an unreliable source of cash. On a cash basis, the provincial government has actually been in debt each year since 2005. That means new borrowing to add to the burden of public debt.